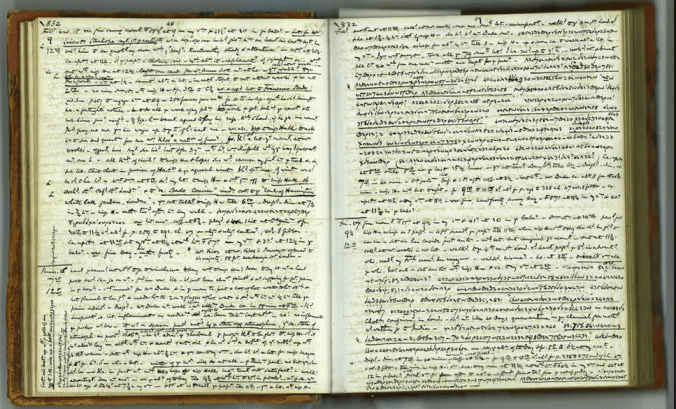

Anne Lister’s Coded Diary

Part 3 in the series.

Read Part 1: “Don’t Burn your Diary! Why you shouldn’t destroy your personal writing.”

Read Part 2: “But my diary is silly or shameful. Common arguments for destroying personal writing, and why they are unconvincing.”

Disclaimer time: I am neither a lawyer nor a conservationist. You should consult a lawyer, estate planner, or conservationist to receive legal advice about your pre-death planning, including the preservation of your diaries, which I address below.

So, you’ve realized that you need to make some plans to guarantee that your diaries, journals, letters, or other private papers are disposed of the way you want them to be, upon the event of your death. But, what do you do? Standard pre-death or estate planning focuses on medical care, finances, and distribution of property; it does not typically take into consideration things like diaries. Yet, there are steps you can take to make sure your wishes regarding your diaries are recorded and respected.

Please note: my recommendations refer most directly to material diaries or journals, not digital ones. Advice regarding what to do about computer files, social media accounts, or online life writing in the event of death can be found at the Library of Congress and the New York Times. I’m more concerned with that box of diaries you’ve got shoved in the back of your bedroom closet, and that your heirs will have to decide what to do with after you’ve died.

Keep your old diaries in archival appropriate conditions. This is something you should do now. Get an acid-free storage box or boxes. Keep it in a safe, dry place. Make sure it’s properly labeled so it won’t get misplaced or thrown out by accident. Tell someone you trust where it is and what’s in it. Give your writing the value it deserves.

See also: Library of Congress: Collections Care

American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works: Taking Care of Your Treasures

Jackson, “Taking Care of Your Personal Archives” (The Atlantic, 2010)

Tell someone what you want done with your diaries. Like all pre-death planning, what’s most important is communicating your wishes to someone who will survive you, and who you can trust to implement those wishes. This may be a family member, a trusted friend, or a lawyer. Write down your wishes. A written statement carries more legal weight than an oral request. Make sure your written statement is with your other legal paperwork: your will, living will, Durable Power of Attorney, etc. Be as specific as possible about what you do or do not want done with your writing. Be reasonable in terms of what you request. Planning ahead about such materials is a kindness to your heirs, saving them from having to make difficult decisions in what may be an emotionally challenging time.

Consider donating your diaries to a library, archive, or historical society. Maybe you have friends or family members who will cherish your diaries, keep them safe, and use them as you wished. But I strongly encourage you to consider giving your diaries to a library, archive, or historical society where they can be read and studied by others. Obviously, this recommendation comes from my immense gratitude to the individuals and families who have made diaries available to me and other scholars – and who have enabled us to do the historical and literary research that is the foundation of our scholarly writing.

Stephen Tennant’s Diary 1848

To donate your papers, I recommend you follow the guidelines developed by the Society of American Archivists. Their brochure, “Donating Your Personal or Family Records to a Repository”, provides a thorough overview of the issues to consider and strategies to implement, including the need to sign a “deed of gift” (which they describe here) in order to secure the donation.

Start locally: your local library, university archive or special collections, local historical society, etc. Certain archives exist specifically to collect materials related to certain categories of identity or experience: Holocaust survivors, for example, might contact their local Holocaust museum, and so forth.

But, there are some options specifically for diarists. Although, as I have bemoaned before, there is currently no national American diary archive, there is one in Italy (the National Diary Archive Foundation in Prieve Santo Stefano in Tuscany, the so-called “City of Diaries”) and The Great Diary Project in the UK. European readers might consider either of these locations for their materials.

Consider restricting access to your diaries for a period of time. If you donate your diaries to an archive, you usually have the prerogative to designate whether they will remain restricted from public access for a period of time. This is a good idea if there is material in your diaries that you want to keep private from specific people (say, your family or someone you write about in your diary). For example, you might set a 50 year restriction stating that no one can read your diary until 50 years after you make the donation or after you die. This is something you will discuss with the librarian or archivist who acquires your materials. But remember, you are within your rights to ask for restrictions and, if your diaries are held by an archive, they have the power to enforce it (which a family member may not).

Samuel Reader’s Diary 1854

Give back. It would be appropriate for you to make a financial donation to the archive that acquires your diaries, in light of the role you are asking them to play in preserving and protecting your papers. Libraries are endangered institutions these days, when they should be valued and compensated for the services they provide us. Consider writing a financial bequest to the archive into your will at the same time you are developing your end-of-life plan for your diaries.

Above all: don’t wait until it’s too late, and someone else is obligated to make decisions on your behalf about the fate of your diaries.

Update: I recently finished reading Alexander Masters’ strange and wonderful book, A Life Discarded: 148 Diaries Found in the Trash, which I highly recommend to anyone who is not yet convinced that it’s worthwhile to make arrangements for your private writing, so that it doesn’t end up in a “skip” like the diaries Masters discovered. (Even if his discovery set off an intriguing treasure hunt.)