When you start to look around for writing about diaries, suddenly it seems to be everywhere.

To wit:

Last weekend, The New York Times Style Magazine* featured three mini-essays by writers on their relationships with diary writing: Sarah Manguso, Amalia Ulman, and Heidi Julavits.

This week, the online teen magazine Rookie** published an essay by Zadie Smith on her decision to not keep a diary.

All four essays are very interesting meditations on diaries but here are my two takeaways:

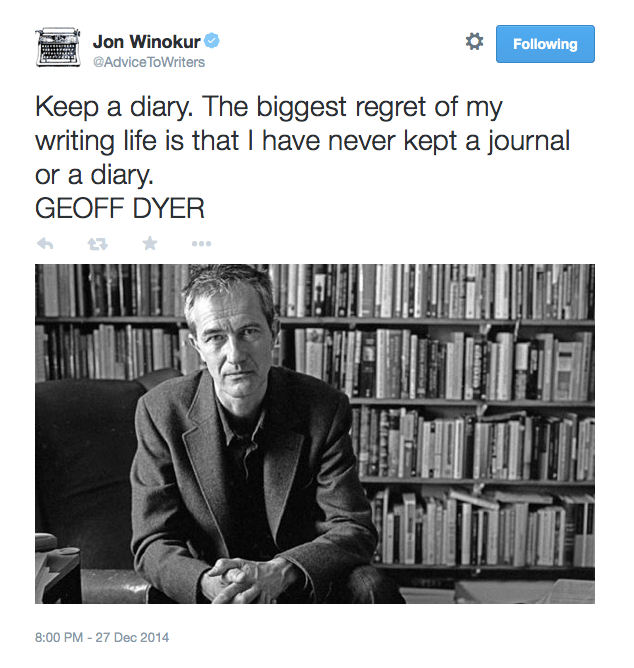

1. So, there are no male writers with something to say about diaries? The association between the diary genre and women (i.e., it’s a form of private writing, therefore one more likely to be practiced by women) has been theorized, deconstructed, and troubled by several generations of literary critics, yet it has remarkable durability. None of the four authors comments on this — they, rightfully, do not see themselves as speaking on behalf of women writers, or women in general. They do not say that diary-writing is women’s work, because it is not. But, this is news that may not yet have reached the editors of these periodicals. I wonder: has anyone ever asked Jonathan Franzen if he keeps a diary?

2. The other notable theme across the four pieces is that the authors actually don’t keep diaries. This is what I am calling the “denial of diary.” Apparently, it is best to speak of diary writing in the negative: I once kept a diary but I don’t any more. I tried to keep a diary but I simply couldn’t. I briefly kept a diary but not really because it was a fictionalized art performance piece. In some ways this is the most writerly of all the poses these authors adopt: apparently, a writer cannot and should not keep a traditional “this is what happened to me” diary. Somehow that genre is too ordinary for a real writer. A real writer will find a way to cleverly invert the terms of the genre to produce something that is indebted to the diary but ultimately rejects the terms of the diary.

I get it. I am sympathetic to the artistic impulse to push against expectations. But, on behalf of all the traditional diary writers, I am a bit defensive. Really, Zadie Smith? Writing in the first person is disgusting, dishonest, artificial, intolerable, laborious, stressful, and, horror upon horrors!, American? (All adjectives that Smith uses.) On behalf of all the people who put a date at the top of the page and write “Today I,” I would like to protest this string of invectives. Diary writing is not for everyone but can you please explain to me why someone who does not write a diary and finds the practice offensive to her sensibilities is the one who is asked to write about writing a diary?

* While I am in ranting mode, I take this opportunity to also comment on how hardily I dislike the New York Times Style Magazine. I subscribe to the Sunday New York Times and I enjoy it immensely. I like feeling as though I have some purchase on what concerns the cultural elite in our country. For the most part, my enjoyment is undiluted by the fact that the cultural elite are also the class elite — I can read about the museums and plays that rich people attend without getting too fixated on their richness. The Style Magazine makes that more challenging. Nothing like 47 pages devoted to advertisements for designer handbags and articles on how $10,000 shirt dresses are the latest thing to put the class status of the New York Times audience front and center. This context probably colors my reading of the essays by Manguso, Ulman, and Julavits: they may not be members of the literary upper-class but appearing within the pages of The Style Magazine makes them appear that they are — which makes me suspicious of their self-deprecating self-representations. Somehow The Style Magazine makes the diary appear simultaneously trendy and passé: something that trend-setters are doing, but only doing with a pretentious twist. Almost makes me want pull a Zadie Smith.

** Rookie actually has an on-going diary column in which five teen girls publish their diary entries in the magazine, as well as several previously published essays about diaries including a wonderful archive featuring pages from their readers’ private diaries. So, I do feel a bit guilty about lumping this periodical into the same class as The New York Style Magazine. They are very, very different publications and the brilliant Zadie Smith can do and say whatever she wants!

Photo Credit: Pushing Time